Raising Learners, Part 1: Responsibility

The first in our “7 Laws of Learning” is the principle of responsibility. This can also be expressed as desire or motivation. It means that the student must have a motive for learning. The motive might not be a sense of responsibility for every learner, but students have a calling that includes the responsibility to learn.

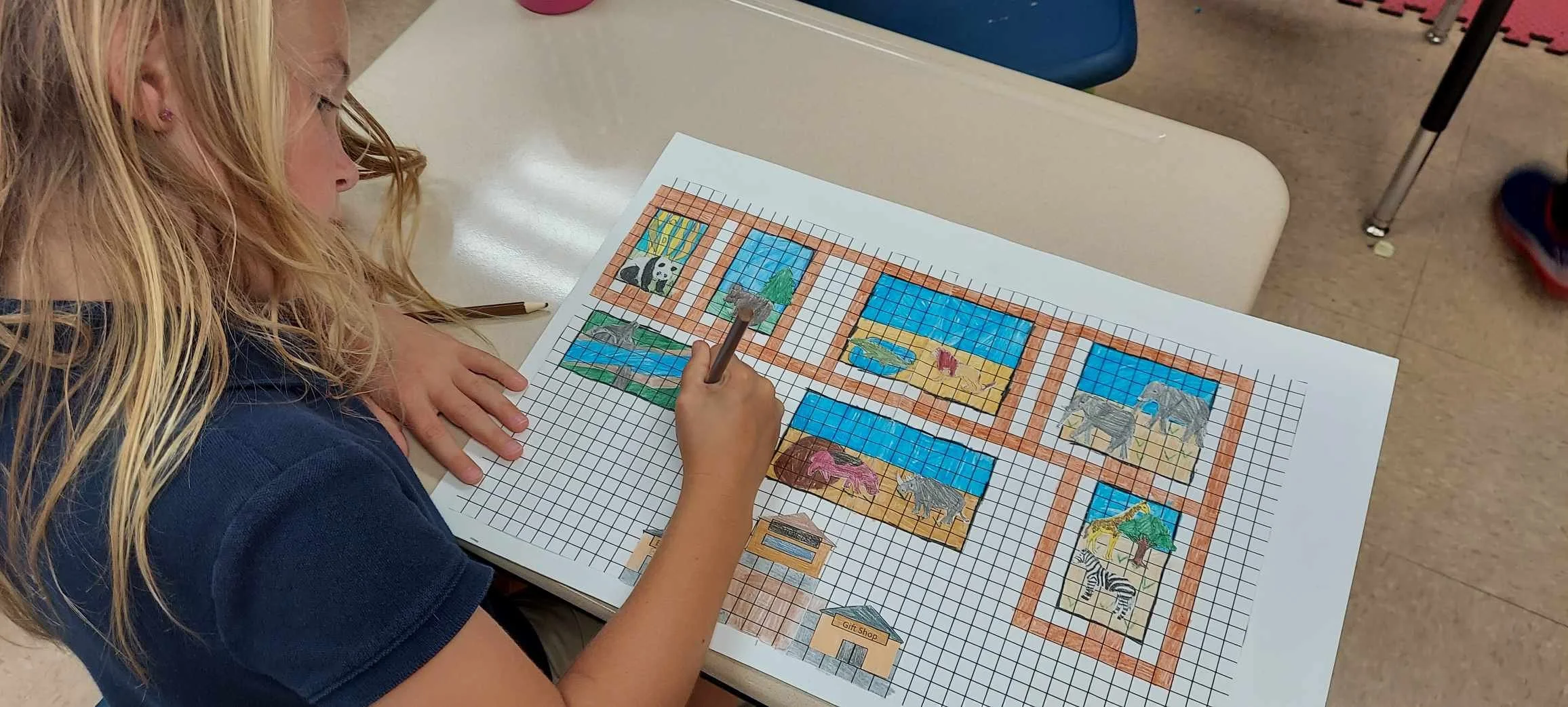

For younger students in the grammar stage, we suggest a rule something like this: “Your job is to learn new things.” This could lead to an argument from a resistant student who says, “You’re telling me things that I already know.” So the meaning of this rule includes a process where the student must patiently review old things while listening, looking, or reading for things that are new.

For older students in the logic or rhetoric stages, we suggest a more articulate way to express the rule. “Approach the learning task with a desire to know and understand more than you currently do.” It contains the same basic content, but touches on that other part of the work more explicitly. The student must somehow figure out what he* currently knows, and identify his opportunities to learn something new.

Certain problems can arise that work against a sense of responsibility. A student may feel coerced into learning. This can happen when a student is expected to start at a new school. Social anxieties, feelings of past failure, or anxieties about expectations and outcomes can overwhelm the student. It might seem that such influences should increase the student’s sense of responsibility, but under an overload of emotional distraction, the student may find that the task of learning is too much to handle.

Sometimes the sense of responsibility finds an obstacle in comfortable social relationships. Less responsible peers or friends may absolve the student for inadequate efforts, providing distractions that require less work and promise more pleasure. Authorities in the student’s life such as adult relatives or older siblings may render opinions on the subject that degrade its value in the student’s eyes. “I had to study that in school, and it did me no good at all. It’s a mystery why they still make you learn it.” Even an envious remark like, “That sounds hard. I never had to do that in school,” can demotivate a student from the serious responsibility of his calling.

A serious student at any age should take some time periodically to consider why he wants to learn. Several reasons are possible. These are not exhaustive, nor numbered in any particular order, but the student could sort them into his own order of priority.

Learning is his job. This is true for every student.

Learning is enjoyable. We are tempted to use the word “fun,” but learning provides a different kind of enjoyment than the fun of playing at any age.

Learning something is an achievement.

Learning something worthwhile adds to a person’s abilities.

Learning makes a person’s understanding of the world more accurate.

Learning exercises the mind. Without it, the mind grows dull and weak.

Some kinds of learning also exercise the body, adding strength, endurance, and a resistance to aging.

Learning to identify bad things can help a person avoid harm for himself and for others.

Learning and appropriating good things is its own reward, and makes a person into a clearer reflection of God’s image.

Learning helps a person better to tell the difference between something true and something false, lending some freedom from ignorance and from deception by others.

Learning beautiful things adds beauty to a person’s life, and increases his abilities to discern and appreciate beauty.

A person who has learned much can acquire the respect of others for such diligence and for the knowledge gained.

Perhaps the reader will think of many other motivations to learn. If you do, please visit our church and school, so that you can share them with us.

*We use the masculine singular pronoun here in the classical gender-indefinite sense, where it denotes either male or female persons. This, in the author’s view, is the most elegant solution. Repeating a phrase like “he or she” is both awkward and unwieldy. Attempting a compromise like “s/he” or using the plural “they” runs against the natural grammar of our language. Switching back and forth between “he” and “she” creates confusion. Unfortunately, the gender-indefinite use of masculine singular pronouns must sometimes be re-taught because it has fallen into widespread disuse, probably due to the misunderstanding that it favors male antecedents. Our solution is to correct the misunderstanding.

The 7 Laws (Rules) of Learning

I set out to draft some “Laws of Learning” that correspond with Gregory’s Laws of Teaching.

There’s a fine little book written by John Milton Gregory in the 19th Century, called The 7 Laws of Teaching. The contents are in line with the teaching practices of classical education, but the title bears a little explanation. The Scientific Revolution saw a common recognition that the universe and human life operate according to discernible laws, like the Law of Gravitation. John Gregory sought to summarize a similar universal truth, which will always remain true.

Gregory’s book is easy to find on the Internet. I was surprised to discover that there is no similar book that teaches the “Laws” or principles of learning as well. After all, a teacher’s craft is useless unless there is a student to teach. Moreover, a warm body does not automatically qualify as a student. That is to say, there is a craft of learning that corresponds to the craft of teaching. When these are pursued in tandem, great things can happen. When one is neglected, there is bound to be disappointment.

So I set out to draft some “Laws of Learning” that correspond with Gregory’s Laws of Teaching. We might prefer these days not to use the word law for this, so the reader has my permission to substitute something like “rules” or “principles.” Out of respect and a sense of coordination with Gregory’s work, I have retained the use of the word law. These are not civic laws, nor moral laws. Like Gregory’s, they are more comparable to the Law of Gravitation. And they are certainly subject to revision, improvement, or adjustment to particular circumstances, as you will see.

We begin with the Laws of Learning stated as generalized principles.

The principle of responsibility, desire, or motivation

The principle of reflection or self-awareness

The principle of regard or attention

The principle of reason

The principle of reason’s restraints or limits

The principle of repetition or review

The principle of reckoning or recall

Each principle states something that should concern the learner. Some relate to the tasks of a teacher, yet the learner’s responsibility can make the difference between failure, moderate success, or high achievement. Rather than explaining each of these principles here, I will illustrate them by recasting them into a form of rules that are worded for a learner of grammar. (See the post, What Is Classical Education?) Because our first example of learning rules is aimed at learners who are in the grammar or elementary stage of learning, they are intentionally simple. For example, Principles 4 and 5 above are combined into rule 4.

Your job is to learn new things.

Ask your teacher after the lesson when you still don’t understand something new.

Think about the new things you are learning, not other stuff.

Check if you are learning things that fit together with what you already know. If they don’t fit, ask your parents or your teacher about them.

Do all of the exercises and practice that your teacher gives you. If you need more practice, you can ask your teacher to give you some to do at home.

Challenge yourself to remember the important things you learn by telling or writing about them from memory.

Comparing these rules to the general principles above, the discerning reader can see that the former list illustrates the latter by putting it into practice. It is likely that some things are left out of this list, which a teacher would like a student to do. They could be added as a local variant. The wording could also be adjusted for the age and comprehension of the learners. These are probably aimed at learners in the 2nd or 3rd grade, but could be applied from first through sixth. Younger learners might find even these rules too abstract, and may need something more simple.

Here is another example of the general principles recast into rules for learners. This time, the rules are aimed at students in the logic, rhetoric, or dialectic stages of learning. Rather than simplifying the principles in application, these rules expand upon them.

Approach the learning task with a desire to know and understand more than you currently do.

Find the limits of your understanding and communicate them to your teacher.

(Respect your teacher, confirm what is taught, and ask questions when this is not possible.)Focus your attention on the frontiers of your knowledge. These may be found through the teacher’s instruction (including media), your own senses, and your mind.

Where possible, use reason to judge the correctness and truth of ideas both new and old. Pursue certainty that your understanding is correct in these areas:

Terminology or vocabulary, consistently understood in a given context within the bounds of acceptable general usage.

(Consider both signification and supposition.)Statements of fact as they express relations between terms.

(Consider both quality & quantity in subject and predicate.)The claims that may or may not be warranted by multiple statements of fact.

Check your reasoning against foundational truths as well as empirical perception. Let your teacher support you. Keep in mind the limitations of each kind of knowledge.

Use repetition to deepen your understanding and confidence.

Study trustworthy expressions of knowledge until you can repeat them from memory.

Practice using new terms in your own speaking and writing.

Construct your own statements of fact concerning what you are learning.

Discuss the validity and truth of your statements and those of others in your class.

Attempt to persuade others and invite persuasion by others.

Study by producing important points from memory and checking your accuracy. Flash cards work well for this. So do friends in a study group.

As opportunity permits, we will have subsequent posts that explore the individual principles in more depth. We will also begin a dialogue about them with the goal of explaining and even refining these principles for the benefit of each individual student and the learning task in a Christian school or a Christian household.

What Is Classical Education

It is an approach to education that says every subject has building blocks which must be known to understand the subject (its Grammar). Once we learn these we learn how they work together (its Logic), and then we learn how to explain it to someone else (Rhetoric). The goal of teachers is to guide students through these parts and teach them when appropriate.

The classical approach to education recognizes three stages of child development, commonly referred to as the grammar, logic, and rhetoric stages. In each stage for a given subject, students are taught what they are best prepared to receive. For example, in the grammar stage, usually kindergarten through about 5th grade, when students are fine-tuned by their Creator to memorize facts, the classical educator encourages them to feast on the facts, the grammar, or building blocks of elementary subjects. As students mature, they grow into the logic stage. Here they begin to move beyond the mere memorization of facts as they ask more “why” questions, and naturally become more interested in debating ideas, using reason to problem solve, and in general, start to understand how the facts they learned in the grammar stage are related to one another. As students enter high school they are ready to tackle the rhetoric stage. Here they focus on persuasive, eloquent communication of thoughts and ideas. This builds on their reasoning skills and uses the building-blocks of the grammar stage.